It’s not clear what’s driving that shift, but doctors say highly contagious variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus are undoubtedly playing a role

Article content

Younger people are getting more severely ill with COVID, and more quickly, prompting desperate “rescue” interventions for people as young as 22 at one Toronto Hospital.

On Monday, 17 people with COVID-19 were connected to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, at Toronto General Hospital, the highest number since the pandemic began. Their ages ranged from 22 to 61. Four are in their 20s or 30s.

“Certainly, we’ve seen a shift in the kinds of patients that we’re seeing coming to the ICU in this wave,” said Dr. Eddy Fan, medical director of the Extracorporeal Life Support Program at Toronto’s University Health Network, or UHN. His ECMO unit, the largest in Canada, is also a provincial referral centre

In wave one and two, most of those put on ECMO because of COVID-ravaged lungs were older, in their 50s and 60s, with chronic health problems. Now, they’re younger, many previously healthy.

Advertisement

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

What’s also different is how swiftly some people are progressing from sick, to mortally ill.

In earlier waves, ICU doctors saw a typical pattern among patients, said Dr. Niall Ferguson, head of critical care medicine at the UHN. “They were sick at home for a week, sick at another hospital for a week, then intubated and on a ventilator for a week, and then they got bad enough to need to come to us.”

People are now getting to that state in a matter of days, not weeks. “That’s been a very clear shift,” Fan said.

A new briefing paper released Monday evening by Ontario’s science advisors shows that the percentage of COVID-19 patients in the province’s intensive care units younger than 60 is about 50 percent higher now than it was prior to the start of the last province-wide lockdown at the end of December — a trend driven by fast spreading “variants of concern.”

Advertisement

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

On social media, doctors are describing previously healthy people “in the prime of their lives” on life-support with COVID. “This wave is worse than a year ago. Worse than January. They’re younger. They’re sicker,” Dr. Shankar Sivananthan, a critical care doctor with the William Osler Health System, a hospital serving Brampton and North Etobicoke tweeted last week.

According to Ontario’s COVID-19 science advisory table, the new variants now account for 67 percent of all Ontario SARS-CoV-2 infections. Compared with earlier variants, the new mutations roughly double the relative risk of ICU admission and increase the risk of dying from COVID-19 by 56 per cent.

The variants have picked up a mutation that makes it easier for the virus to latch onto receptors on human respiratory cells. “Clearly there is something that is making them both more transmissible and able to replicate more quickly,” Ferguson said.

Young adults are much less likely than older people to become seriously sick with COVID. But their risk of needing ICU care or dying is not inconsequential, said Dr. Scott Solomon, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and senior physician in the cardiovascular division at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Advertisement

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

Solomon is a co-author of a recent analysis reported in JAMA Internal Medicine. He and his colleagues analyzed the medical records of 3,222 people, aged 18 to 34, admitted to American hospitals with COVID in the spring wave of 2020.

In all, 21 per cent required intensive care, 10 per cent mechanical ventilation and three per cent died. The death rate was lower than that reported for older adults with COVID, but roughly double that of young adults with a sudden heart attack. Severe obesity, high blood pressure and diabetes increased the likelihood of severe “outcomes” from COVID in the young. So did being male.

“The demographics of COVID-19 infection are clearly changing from the spring (of 2020),” Solomon said. In Canada, new infections are highest among the 20- to 29-year-olds, a more mobile and socially active group, but whether the new variants alone are contributing to more younger people being hospitalized “is hard to know for sure,” Solomon said.

Advertisement

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

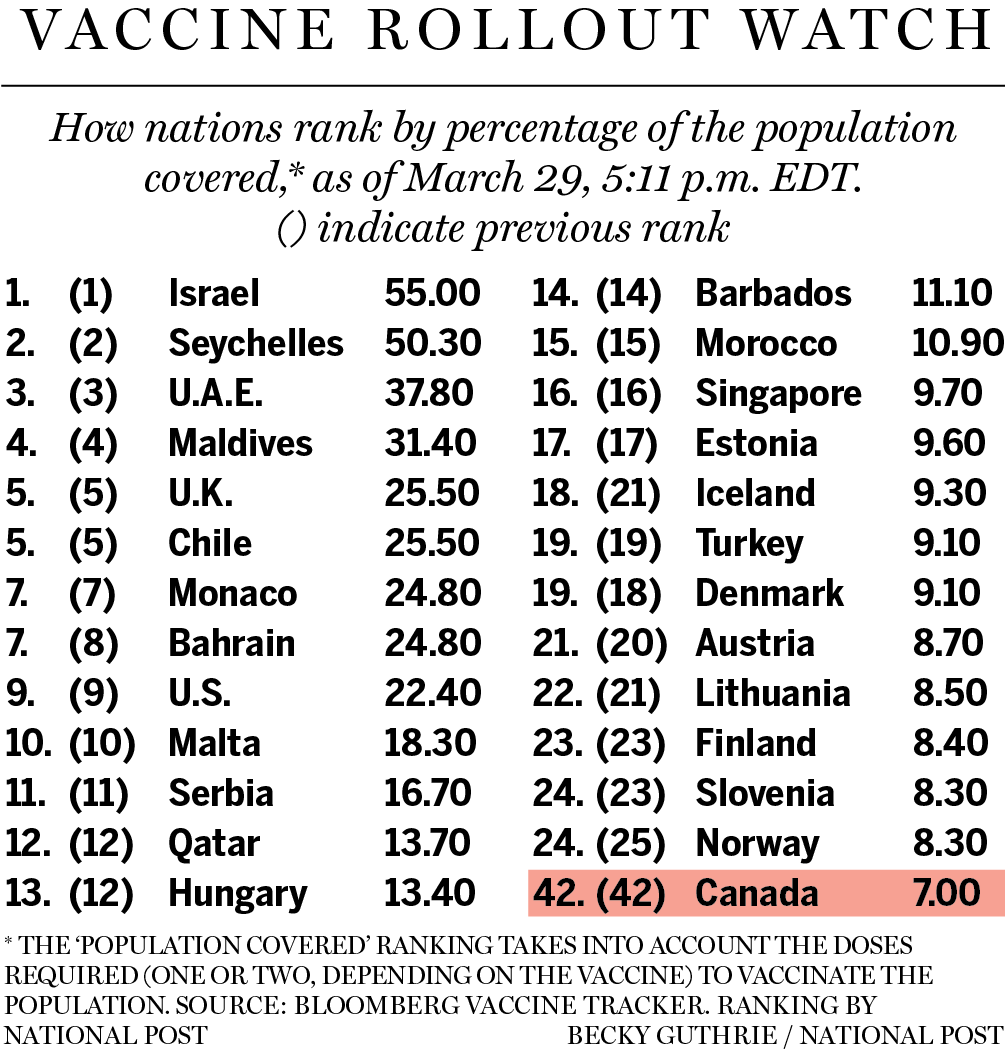

More elderly people are being vaccinated. Remove the most vulnerable, and the face of the pandemic changes. “These are not simple metrics to analyze, because there are multiple parameters that are influencing what we are seeing right now, and we have to be very careful to make these statements that, ‘Oh, yes, the younger people, we’re seeing more of them in hospital,’” said the University of Ottawa’s Dr. Marc-André Langlois, who is helping spearhead a new national Coronavirus Variants Rapid Response Network. “We’re seeing more of them because we’re not seeing as many elderly in proportion.”

Mutational changes are making it easier for the virus to bind to human cells, Langlois said. “But why the younger adults? Why is it not affecting just everyone in the same way, in the same proportion? There are layers to that complexity that are still poorly understood.”

According to data from Critical Care Services Ontario, on March 21, people under 29 accounted for fewer than one per cent of COVID-related ICU admissions in Ontario; 30- to 39-year-olds accounted for 5.5 per cent. Those aged 50 to 79 accounted for 75 per cent of COVID-related critical illness ICU admissions. The height of the curve (29 per cent of ICU admissions) was among 60- to 69-year olds.

Advertisement

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

It’s not clear how those numbers compare to a few months ago. The CCSO does not make its data public. Nationally, as of March 26, there were 125 reported COVID-related deaths among those aged 40 and younger, accounting for 0.6 percent of all deaths.

“In the end, this is a numbers game — the more individuals in the younger age group who get infected, the more will have severe disease requiring hospitalization and potentially intensive care support,” Solomon said. All of which makes masking, distancing and avoiding gatherings (bars, nightclubs, parties) that can fuel transmission important until vaccines are rolled out to younger people, he said.

Variants are dominant in parts of Quebec, and Saskatchewan. The Ontario Hospital Association has warned ICU beds are at the saturation point.

The ECMO teams in Toronto are also being stretched. Sometimes referred to as a medical “Hail Mary,” ECMO is used when all other options have been exhausted.

With ECMO, blood is drained from the body through a large tube or cannula inserted into the femoral vein in the groin, circulated through a machine that adds oxygen and cleans out harmful carbon dioxide and then pumped back into the body via a large tube in the jugular vein in the neck.

Advertisement

Story continues below

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content

Rather than forcing the injured lungs to work with a ventilator, the idea is to let the lungs rest while trying to heal.

People are deeply sedated, their muscles paralyzed, and in a coma. The risk of death is about 50 to 55 per cent.

“It’s been challenging whether they’re 20 or 70,” said Fan.

“We’re all looking for the light at the end of the tunnel,” he said. “But we’re really concerned that, before we reach that with vaccination, we could get to the breaking point.

“What will we do when we get that next call for a young patient who needs ECMO and we don’t have the staff, the space or the machine to provide that care? What will we do then?”

• Email: skirkey@postmedia.com | Twitter: sharon_kirkey